The Family Secret Uncovered by a Writerã¢â‚¬â„¢s Dna Test

T ake a look at your reflection. What do you meet? Who do yous call up you are? When the writer Dani Shapiro was a lilliputian girl, she would sneak down the hall late at night once her parents were asleep, the meliorate to stare at herself uninterrupted in the bathroom mirror. She felt, though she would not accept been able to articulate this at the fourth dimension, unlike – a animal apart. Perchance if she gazed at herself for long enough, a new face would sally from behind her own: a truer one, a face that would better reflect her sense of herself.

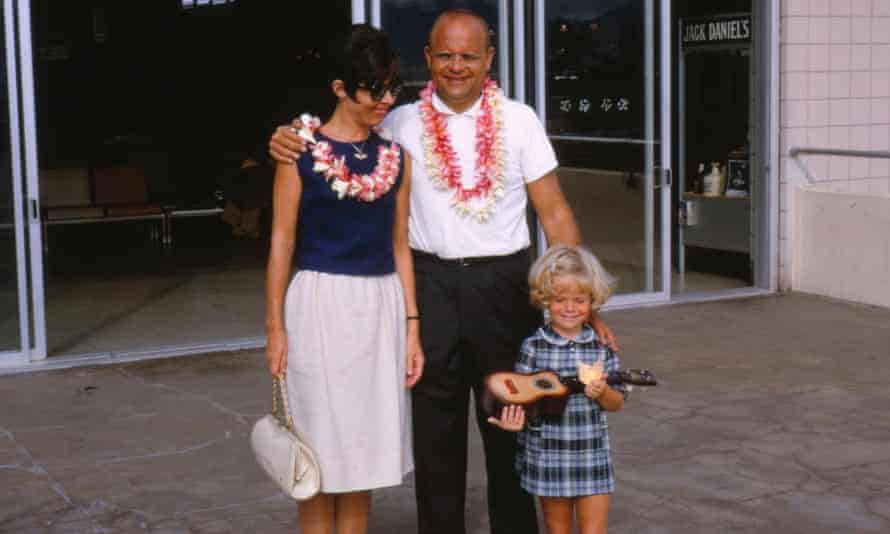

As she grew older, this otherness – a disconnect she carried with her all the fourth dimension – grew more and more powerful. It was, she says, every bit though she was "trapped on the other side of an invisible wall, separate and cut off" – and even so, she had no idea why. In the New Bailiwick of jersey neighbourhood where she grew up, the only child in an Orthodox Jewish family, she would wander the streets with her poodle, hoping to exist invited in by neighbours. She wonders now if she wasn't looking for a new family. Did other people meet her every bit dissimilar? Well, they were certainly struck past her appearance. Shapiro has white-blonde hair and blue eyes. One day in the belatedly 1960s, a family friend, Mrs Kushner – the future grandmother of Jared, married man of Ivanka Trump – pulled her to one side. Mrs Kushner had lived in Poland during the state of war. "We could take used yous in the ghetto, little blondie," she said, gripping her arm. "You lot could accept gotten usa bread from the Nazis."

Shapiro is the author of several bestselling memoirs, her stock-in-trade the public unpicking of life'due south more complicated knots. "I've e'er tried to make meaning out of things that are difficult," she says. "To attempt to guild the chaos."

Simply down the years (she'southward in her 50s now), she'd besides come to accept that there was a mystery at the centre of her life: something on which she couldn't put her finger. In June 2016, yet, the mystery was solved. Shapiro inadvertently made a discovery, at which point her otherness, and her blonde hair, all of a sudden made sense – though everything else she thought she knew now crumbled to dust.

"An air of unreality settled effectually me," she writes in her new memoir, Inheritance. "I was stupid, disbelieving. Nada computed." Who do you think you lot are? This was a question that she both could, and couldn't, answer.

In 2016, Shapiro's parents were no longer live: her loving begetter, whom she adored; her difficult mother, to whom she was never close. That summer, her married man, Michael, curious almost his origins, had sent away for ane of the DNA-testing kits that are at present the US's most pop holiday gift (terminal year, 12m were sold; in full, some 26m people have taken a exam, calculation their Dna to the iv leading commercial ancestry databases), and one night the two of them spat into 2 vials. Weeks later an email arrived, containing their results. She and Michael were puzzled by hers: co-ordinate to the Ancestry website, her DNA was only 52% eastern European Ashkenazi, and the residual a smattering of French, Irish gaelic, English and High german. Simply they were inappreciably concerned – until they decided to compare her results with those of her half-sister, Susie, at which point Michael grasped that the two women were not, in fact, related at all.

This could hateful only 1 of two things: either Shapiro's father was not Susie'southward male parent, or he was not hers. In her gut, Shapiro knew immediately that he was Susie's father. Susie looked similar him, whereas she looked like no one in their family. Just how could this be? Her dear dad, her soulmate. After this, things moved chop-chop. On Beginnings, a starting time cousin – i unfamiliar to Shapiro – was listed. Information technology didn't take much earthworks to discover that his mother had two surviving brothers, one of whom, a md, had been a medical student in Philadelphia, the metropolis to which, Shapiro at present remembered, her parents had once travelled for fertility treatment (her mother had mentioned this only twice to her daughter in her lifetime, and always in a way that brooked no discussion). Was it possible that this man – in her book, Shapiro calls him Ben Walden – had been a sperm donor back in the day, and his sperm "mixed" with that of her father? (Clinics, then unregulated, often used this practice to improve their results; patients were told to go home and call up no more most information technology.) Yes, it was more than possible. Having found him online, she watched a video on his website in which he appeared before her: a man with her colouring, her jaw, her eyes, her vocalization and her hand gestures.

On my own computer screen – we talk via Skype; she is in a hotel room in New York, a stopping point on her Usa volume bout – I encounter Shapiro smile. In the moment of her discovery, she felt traumatised and alone. Why had her parents gone to their graves carrying and then huge a secret?

Simply she knows now that she really isn't alone. "This is my 10th book," she says. "And I've never experienced anything like it. On tour, every event has been wall to wall. It'due south fascinating. I can almost option them out at present. In every audience, there is a significant number of people who take discovered family unit secrets of their own: adoptees who were never told; donor-conceived people who never knew; parents who made a decision not to disclose the truth to their children, but who now realise that is no longer feasible; older men – not my usual kind of reader – who have been anonymous donors, and who take either already been contacted [past their biological children], or who believe there'due south a proficient gamble they might be."

Shapiro believes that in the US there is currently "a kind of epidemic" in terms of the numbers of people who are learning the truth about their identity. "The kits are so pop. Information technology is a chip of a national obsession. The statistic in the industry is that approximately 2% of people who take a Deoxyribonucleic acid test detect an NPE – that is, to use the terminology, they are Not Parent Expected, or a Non Parental Event. If 12m kits were sold in the US last twelvemonth, then around 240,000 people have discovered their parent is not their parent – and they're only the ones who've taken a test."

Her book, Shapiro thinks, speaks to this "epidemic", the literature around donor insemination being surprisingly scant – and though Inheritance is a highly personal book, one that seeks to tell but her story, in the months since she finished writing it, she has grown ever more focused on what she regards as the long-ignored ethical issues involved in donor insemination.

"In my parents' time, there was no regulation. I've spoken with many people who made the discovery they were donor-conceived, and then almost immediately plant 27 half-siblings, 42 half-siblings. This is happening all the fourth dimension. Only even now, the state of affairs is not much amend." In the UK, donors can no longer be bearding (the law inverse in 2005). Merely in the US and Canada, it's yet permitted.

"Many donors all the same tick the anonymity box. That needs to alter, partly considering of the consequences for their biological children – my book is instructive about what it'due south like to discover you're the kid of an bearding donor – but likewise considering they will be found. There'due south a basic misunderstanding about Deoxyribonucleic acid testing. My [biological] father had not had a Deoxyribonucleic acid test. But a nephew of his had and so I found him. Anonymity is over. We need to ask if the guarantee of anonymity fabricated by sperm banks is nonetheless valid when the world has inverse – and the science has inverse."

In recent weeks, Shapiro has spoken at the bio-ethics departments of both Harvard and Stanford universities. "This is complex. What is the moral responsibleness of someone who one time donated sperm? And what is the moral responsibleness of someone who discovers they were conceived in that way to the donor? A few decades from now, people volition say, 'My God, I can't believe it ever happened that way.' Scientific discipline is going to force us into a place where there can't be these secrets. Simply right now, we're dealing with a tidal wave."

Shapiro is lucky. Her feel, after the initial shock, was positive. She wanted to run across her biological father and, after some hesitation, he agreed. They got on well and their relationship – a warm friendship – is ongoing. "He did the right matter," she says. "He is a lovely human being beingness and I recognise aspects of myself in him. But I've heard a lot of stories, and they're not all good. If I'd found my biological begetter, and he was hateful and had different politics from me and lived a life I didn't recognise, that might have been dissimilar. Or if he had not wanted to meet me at all. That would also accept been hard." Coming together Ben has helped her to feel, at last, "like a complete person".

Nor did her discovery, ultimately, alter her feelings for the homo she grew up with. "I hated it when people said to me: 'Your father's still your father.' But when people said: 'He couldn't have loved you more,' I knew that was true. At commencement, it was difficult to move by a sense of having been betrayed by my parents, simply I've come to feel them equally creatures of their time. This could not take been easy for them." Their infertility, and the clandestine they shared, has shed new light on their relationship. "My father was certainly sad and beaten downward – before he married my mother, he'd been divorced and widowed – and my female parent did accept a personality disorder. But what they went through to excogitate me and what they then did to pack away the noesis of information technology – that only poured gasoline over the whole thing. Information technology had a not bad bargain to do, I see now, with my father becoming a shadowy figure and with my mother's rage and contempt for him."

Shapiro was closer by far to her father, who was not biologically related to her, than to her mother, who never stopped reminding her daughter that information technology was to her that she owed her existence. "But if annihilation, I love him more than before. I talk to him more; I experience him around me more. This cognition has led to an evolution of something I already felt: the sense that who we dear, and feel connected to, sometimes has to do with biological science, and sometimes not. I'm less and less interested in the prescribed rules about these things. My parents created a myth. They worried what people would recall, but there was likewise the fear that their child wouldn't beloved them equally much if she knew the truth – and I tin can't imagine such a thing."

This sense extends outwards, to other members of her family. The start time she saw her beloved aunt Shirley and her cousins on her father's side afterwards her underground was out, she felt closer to them than ever. "There was a truth between u.s.," she says. "This profound openness."

And what of her Jewishness? We all make narratives of our lives: stories nosotros've inherited, or told ourselves, and burnished downwardly the years. If nosotros have grown upwards in a particular community, it can be central to our sense of identity. In Inheritance, Shapiro describes all that her Judaism means to her: the Hebrew prayers that constantly play in her head; the portraits of her relatives that hang on the walls in her hall; higher up all, the foreign shame she felt when people were apt to insist she did not look Jewish. "I had a much more complicated relationship with that than I acknowledged," she says. "Not looking Jewish was somehow perceived every bit flattering, and that felt uncomfortable to me."

Does she feel differently about this aspect of her identity at present? Yes, but not in any of the ways y'all might look. "After I finished the volume, I was at a gala dinner in New York organised by a Jewish organisation," she tells me. "And there, I caught a wink of myself in the mirror in the hotel ballroom, and saw myself the way other people see me for the first fourth dimension. In that location is a hole-and-corner unconscious language people accept: it's very human to notice the familiar – we exercise it whether nosotros like it or non. I'd always been treated by my tribe equally other, but now I understand why, and it's liberating." She hesitates – uncertain, perhaps, that I'll understand. "What I hateful is that I'm free to be as Jewish as I want to be." Shapiro isn't one for happy endings; she is not a person who ties things upwards with "corking bows". But the rabbi who told her that her discovery was, pinching from Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "a gauntlet with a souvenir in it" was correct.

Inheritance is dedicated "to my begetter". That she doesn't say which one speaks volumes: those who like to insist that blood is ever thicker than water should read her book, and let their own hearts slowly and gently expand.

Inheritance past Dani Shapiro is published past Daunt Books at £9.99. Buy it from guardianbookshop.com for £8.79

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/global/2019/jun/09/dani-shapiro-science-will-bring-an-end-to-these-family-secrets-inheritance

0 Response to "The Family Secret Uncovered by a Writerã¢â‚¬â„¢s Dna Test"

Post a Comment